A selection of photos from our new shop and some of the retail products available.

Author: Geoff Hopkins

Open Tea Tasting: September 2019

Once a month we host an open tea tasting event at our shop in Ho Chi Minh City (2B1 Chu Manh Trinh in District 1). Usually, the event is held in our tea room/ studio but this month it was out of action due to burst pipe – so we had to move outside into the shop area.

This month’s theme was a look at our new wild oolong teas as well as trying two one bud and one leaf white teas.

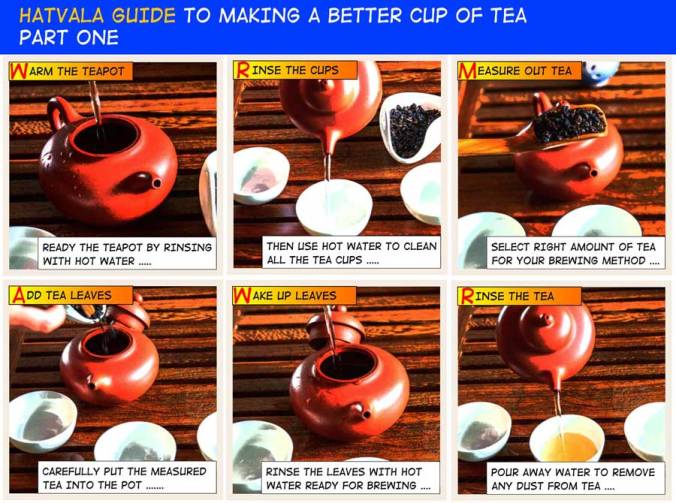

The Hatvala Guide To Making Your Cup Of Tea

Introduction

There are many factors that can affect the enjoyment of a cup of tea. Where you are, who you are with, what your mood and expectations are can all play a part in the level of satisfaction. However, at the center of everything is the tea itself and how well it has been prepared. Maybe it is impossible to ever achieve perfection but excellence is available to anyone prepared to devote the time and energy and who is willing to experiment.

Western Versus Eastern Brewing Method

Below we refer to western and eastern methods of making tea. This is mainly for ease of reference rather than a hard and fast set of cultural rules. For the eastern method we imagine tea made in a small pot for sharing with family or friends in small cups over many infusions. The western method envisages making tea to drink in a larger cup or mug; perhaps to sip while you work or relax.

There is no right or wrong way to enjoy tea – just whatever works best for you!

The Things That You Will Need

Tea – explore the world and discover the incredible range of loose leaf teas that are available. As with most products, there is a broad range of prices and qualities and price does not always equal quality. Many vendors source teas only from large wholesale importers and miss out on the more unique and small batch products that are available. If you can, try to find reliable vendors that specialize in teas from particular countries or areas. Always be curious, willing to try something new and to ensure that your tea is from a responsible and sustainable source.

Water – find the best practically available water that you can. In some places this can be straight from the tap or faucet (preferably filtered). If you prefer to use bottled water then spring water usually produces better results than mineral water (too hard/ mineral rich) or distilled water (too soft – making a flat tasting tea).

Brewing Vessel – the most suitable materials for your brewing vessel (e.g. tea pot or gaiwan) are porcelain, ceramic or glass – something that will retain heat well and not alter the taste of the tea. Ideally, you need as much tea and water to be combined as possible during brewing; enough room for the leaves to unfurl/ expand; and an ability to separate leaves from the tea completely once brewing is complete. For convenience it is possible to make tea in a mug/ cup with a removable infuser provided that the infuser is large enough.

The Things That You Need To Do

There are three key variables in tea making: the amount of tea to water ratio; the temperature of the water used; and the time allowed for brewing. It is important to take care about these but no need to be obsessive about it. The table below can be used as a guide when making tea, but as we all have different tastes and preferences feel free to vary to suit your needs.

|

Tea Type |

Temp |

Western (300 ml water) |

Eastern (200 ml water) |

||||

|

Weight |

Time |

Re-use |

Weight |

Time |

Re-use |

||

|

Green Tea |

85C/195F |

4g |

2 min |

x 4 |

5g |

50 sec |

x 4 – 5 |

|

White Tea |

80C/186F |

4g |

2 – 3 min |

x 3 |

4.5g |

50 sec |

x 3 – 4 |

|

Oolong Tea |

95C/203F |

6g |

2 – 3 min |

x 3 |

8g |

1 min |

x 4 – 5 |

|

Black Tea |

100C/212F |

4g |

2 – 3 min |

x 3 |

5g |

1 min |

x 4 – 5 |

|

Dark Tea |

100C/212F |

6g |

2 – 3 min |

x 5 |

8g |

1 min |

x 7 |

|

Flower Tea |

85C/195F |

4g |

2 – 3 min |

x 3 |

5g |

50 sec |

x 4 – 5 |

Before starting it is recommended that all your pots, cups and utensils are clean and warm and that you give the tea leaves a quick rinse with hot water before brewing.

Amount of Tea – Loose leaf tea comes in all shapes and sizes making weight the only true guide – a teaspoon of oolong tea will be very different from a teaspoon of white tea! Over time it is possible to judge how much of any particular tea provides the sufficient weight.

Temperature of Water – absolute precision is not required but the chances of creating a tea with too much bitterness or astringency are increased when using water that is too hot for the leaves e.g. white, green and oolong teas. If you do not have a temperature controlled kettle then some simple observations are possible:

for white and green tea – when bubbles first start to appear on the water surface;

for oolong tea – when bubbles begin to break the water surface more vigorously;

for black tea – when water reaches a rolling boil.

If you have gone too far, don’t worry, just let the water stand for a few minutes to cool. However, re-boiling the same water many times is not recommended as it depletes the oxygen content.

Time – this is self-explanatory and the easiest way to vary the strength of your tea. With good leaves being able to provide multiple infusions it may be necessary to increase the brew time as you progress to maintain consistency.

Follow these simple steps with some care and you should make the most of your tea every time. Happy Brewing!

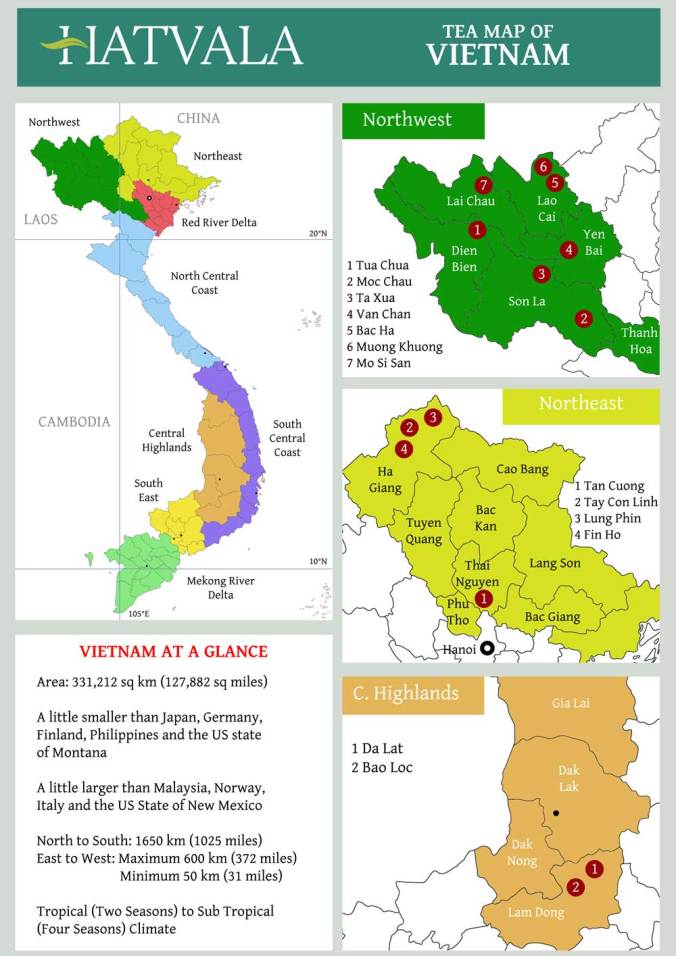

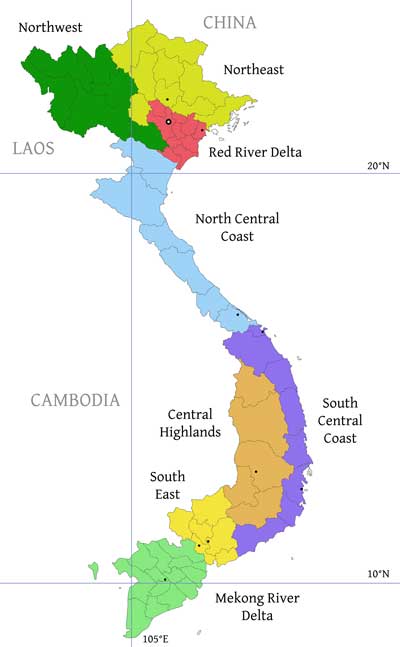

Vietnam Tea Map

Son La Gallery

Different Types of Tea

A Handful of Tea Leaves

For the casual observer it is safe to assume that all types of tea are produced from a common source material, the leaves of the camellia sinensis plant family – although there are some minor variations to this if my understanding of current taxonomy beliefs is correct. The differences experienced between tea types being due to the either the standard of leaf harvesting or processing methods.

Teas are most often classified into 6 broad types: Green, Black, Oolong, Yellow and Dark. Probably the most significant difference between types is the degree to which leaves are allowed to oxidise during processing (as this is where the greatest chemical changes occur), but it does not tell the whole story. In simple ‘elevator pitch’ terms (but not necessarily technically correct) green tea is un-oxidised, oolong tea is semi-oxidised and black tea is fully oxidised. White, dark and yellow teas can be regarded as variations or extensions of these three types.

There are some who have very fixed views on whether individual teas belong to a particular category type or not often based on their own prejudice or expectations. There are most definitely overlaps at the boundaries between each type. Personally, I see it more as a guide to what you might expect and have never come across any prescriptive rules stating that a particular tea must be processed in a particular way. I look at it in the same way as a movie being assigned to a specific genre. If you went to see an Action movie and it had a touch of Romance then who cares. But if you went to see a Sci-Fi and it turned out to be a Musical then something has gone very wrong. I believe it is best to remain open-minded provided there is not an intention to misrepresent or mislead. A tea should be judged on your overall experience rather than in comparison to a checklist of features.

Tea Leaf Styles

Before continuing we will pause to consider some of the terminology used in tea circles, specifically in relation to ‘oxidation’. Oxidation is a chemical reaction that occurs when harvested leaves come into contact with oxygen. The more of the leaf structure that is exposed to oxygen the greater the degree of oxidation. Oxidation can be prevented or stopped by heating the leaves at the desired time; a process known as kill-green, firing or denaturing. In the early days of tea processing it was believed that this process was, in fact, fermentation and even now the words ‘oxidation’ and ‘fermentation’ are used interchangeably. To add more confusion is the fact that a more accurate description of the process should be ‘enzymatic browning’ rather than oxidation but as oxidation is the most commonly understood I will continue to use it here.

A final complexity is with dark teas which are typically referred to as post-fermented. For these teas further chemical changes take place at the end of processing as a result of microbial action. While fermented or post-fermented teas are the generally accepted ways of describing such teas it would be more accurate to describe it as microbial ripening

We will consider the detail and intricacies of Tea Processing at another time and for now content ourselves with a very brief introduction and overview to each type:

Green Tea (genre: Drama) – a short physical wither after which leaves are fired within a few hours of harvesting to deactivate the enzymes that cause oxidation and the chemical changes that this produces. Firing can take the form of steaming, baking or frying. The leaves are then generally rolled and dried but maintain much of their green colour. Tea flavours are typically grassy, vegetal or floral.

Black Tea (genre: Action) – subject to a prolonged controlled physical and chemical wither prior to a hard rolling (maceration) that breaks down the leaf cell walls to facilitate oxidation. Once oxidation is complete the tea is dried, graded and sorted. Black teas are often brisk, full bodied with flavours tending typically towards malty and chocolate. In China, black tea is referred to as red tea which is a better approximation to the colour of the brewed tea.

Oolong Tea (genre: Adventure) – undergo physical and chemical withering before being shaken/ bruised at the edges to promote oxidation. The degree of oxidation in Oolongs can vary greatly and are typically quoted as being between 20% – 80%, which is often an estimate in any case. The complexity and variety of flavours in Oolongs is vast and is further developed by the practice of roasting or ageing the finished tea.

White Tea (genre: Romance) – mainly just withered and dried although it is sometimes lightly rolled for shape. Usually described as minimally processed, this is only true in terms of process steps rather than the time and degree of attention required. Oxidation occurs during extended wither but is controlled through drying rather than firing. Frequently but not always made from leaf buds only while the inclusion of young leaves delivers stronger flavour.

Yellow Tea (genre Sci-Fi) – a variation of green tea, yellow tea undergoes an additional step of moist heaping or smothering under cover after firing and before rolling. The resulting tea is more mellow and without the grassy aroma of green tea. It is the least common of tea types.

Dark Tea (genre: Epic) – aka post-fermented tea of which the most famous is Pu’erh tea. Dark tea will usually start life as a simple green-like tea but allowed to ferment (microbial ripening) as a post processing activity. A more recent development has seen accelerated ripening employed by heaping fired leaves under covers to promote microbe activity. This is referred to as ‘cooked’ Pu’erh while the more traditional method (i.e. without accelerated ripening) is known as ‘raw’ Pu’erh. Earthy and woody flavours are typically associated with post-fermented teas.

Flavoured Tea (genre: Musical) – not really a type of tea but an increasing trend is flavoured teas. Tea leaves have a great capacity for absorbing flavour and there are a wide range of available, from the more traditional floral scents (e.g. jasmine) to more exotic and contemporary flavours. Many purists turn up their noses at scented teas but they can be delightful. The majority of modern flavoured teas, however, are artificially scented.

Blending Tea With Flowers

Here in Vietnam all types of tea are produced albeit in different quantities and qualities. The exception is any yellow tea as described above although you will come across those who say they are making trà vàng (literally yellow tea), particularly in the wild tea growing areas. This, though, is a very basic green tea (no smothering involved) that frequently goes across the border to China for further processing as dark tea.

Oolong tea production is a more recent phenomenon in Vietnam often in collaboration with Taiwanese businesses while dark tea production has long been undertaken but is having something of a renaissance due to increased worldwide interest.

Jasmine and lotus teas from Vietnam have become quite well known in overseas markets.

Yen Bai Gallery

Ha Giang Gallery

Where Tea Can Grow

All of the environmental factors – geography, topography, soil and climate – that affect the characteristics of an agricultural product are collectively known as terroir. Wine snobbery has created a sense of pretentiousness around terroir but there is, unfortunately, no alternative term and terroir plays a fundamental role in determining a tea’s character, as it is for many other agriculture products such as coffee, chocolate and tobacco.

Tea has proved to be a versatile and adaptable plant that will grow in a variety of conditions although it is arguably best suited to those that match its native habitat. Camellia sinensis is a subtropical plant; the subtropics are considered to lie between the tropics (23 degrees) and approximately 40 degrees from the equator. Within these latitudes tea requires a humid subtropical climate where rainfall concentrated in the warmer months rather than dry summer months associated with a Mediterranean climate. Subtropical climates can also be found within the tropics at higher altitudes.

Tea will grow in temperatures above 13C with the ideal range for photosynthesis between 16C and 28C. It prefers small fluctuations in daily temperature and can withstand a frost but not a prolonged or heavy freezing. Typical rainfall in tea growing areas should be 1500 mm – 2500 mm (59 – 98 inches) but can be much higher. Heavier rains will promote quicker growth and affect the chemical content of the leaf. Teas from the dryer months tend to the most sought after for optimum flavour.

Tea can be grown at altitudes from sea-level to 2,500 metres (8,200 feet). A rule of thumb classifies 0 – 600 metres as low grown, 600 – 1100 metres as mid grown and 1100 – 2500 metres as high grown. Tea plants need sunlight but not too much direct sun; at lower altitudes shade trees are often planted to create shade and in some places plants are kept shaded in the weeks before harvest to increase the levels of chlorophyll in the leaf. In higher altitudes with cooler temperatures and frequent mists the need to shade is less urgent.

Tea can be grown at altitudes from sea-level to 2,500 metres (8,200 feet). A rule of thumb classifies 0 – 600 metres as low grown, 600 – 1100 metres as mid grown and 1100 – 2500 metres as high grown. Tea plants need sunlight but not too much direct sun; at lower altitudes shade trees are often planted to create shade and in some places plants are kept shaded in the weeks before harvest to increase the levels of chlorophyll in the leaf. In higher altitudes with cooler temperatures and frequent mists the need to shade is less urgent.

Tea plants do not require dormancy during parts of the year but there appears to be a strong correlation with plants that are dormant during the dryer months and the highest quality of teas produced. Dormancy is triggered by lower temperatures (below 13C) and shorter day length (less than 11.25 hours) and generally occurs at circa 18 degrees from the equator.

Tea favours a fertile, well drained and slightly acidic soil. Roots are intolerant of waterlogged soil which is why tea is often found growing on sloping hillsides or when it is not large trenches are dug between rows. Some of the most sought after (and expensive) teas in the world are grown in mineral rich rocky soils which results in lower yields but unique flavours.

As with all things meteorological there are uncertainties and micro-climates that defy the rules and the presence of mountain ranges can create a rain shadow (such as that found in Sri Lanka) or large bodies of water can create high humidity where it might not otherwise exist and generate a modifying effect that allows tea to be grown successfully; a great example of this is the coastal Rize Province in Turkey.

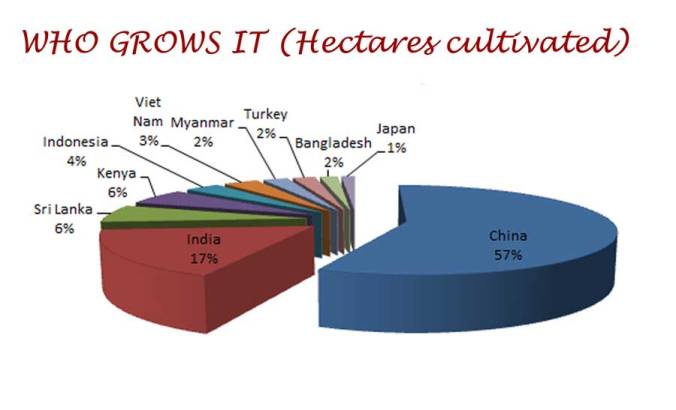

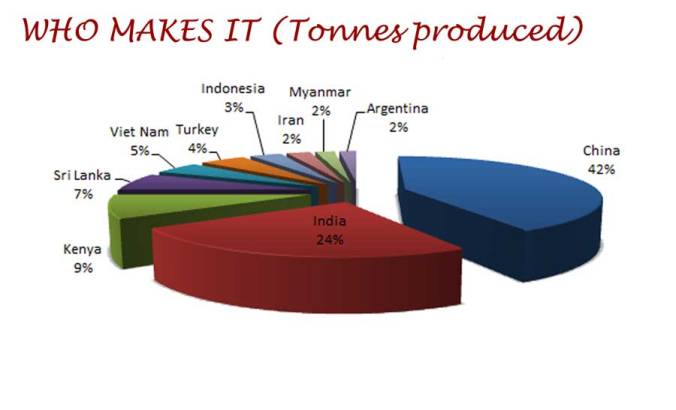

Tea is now grown in over 40 countries around the world with an annual production of over 5 million metric tonnes. The largest tea producing countries in terms of volume are China, India, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Turkey and Indonesia. The last three are difficult to separate and often vary according to whose statistics are being used. Taiwan production is usually included with China for the purposes of published data but would not feature in the top ten on its own with its focus on quality rather than quantity. Likewise, Japan is famous for quality tea production but falls someway behind on quantity.

Tea is now grown in over 40 countries around the world with an annual production of over 5 million metric tonnes. The largest tea producing countries in terms of volume are China, India, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Turkey and Indonesia. The last three are difficult to separate and often vary according to whose statistics are being used. Taiwan production is usually included with China for the purposes of published data but would not feature in the top ten on its own with its focus on quality rather than quantity. Likewise, Japan is famous for quality tea production but falls someway behind on quantity.

The above charts are based on the latest information published (2014) by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. China and India continue to dominate producing 2,100 and 1,210 metric tonnes respectively. More up to date information is available from other sources but is not as comprehensive as the FAO data.

Although volume production is generally confined to parts of Asia, Africa and South America small specialist farms are appearing all over the world with some notable developments reported in places such as the USA, New Zealand, Germany and the United Kingdom.

In Vietnam tea was originally native to the northernmost areas that form the border with China but is now grown in over half of the countries provinces. The Northwest and Northeast of the country have the greatest concentration of tea cultivation although there is also significant production in parts of the Central Highlands (which is also the home for much of Vietnam’s coffee production.)

In Vietnam tea was originally native to the northernmost areas that form the border with China but is now grown in over half of the countries provinces. The Northwest and Northeast of the country have the greatest concentration of tea cultivation although there is also significant production in parts of the Central Highlands (which is also the home for much of Vietnam’s coffee production.)

Areas of wild tea trees can still be found in Dien Bien, Son La, Lai Chau, Lao Cai, Yen Bai and Ha Giang provinces while the heart of commercial tea production is in Thai Nguyen province, just north of Hanoi. The prize for most productive province, however, goes to Lam Dong in the Central Highlands where the area around Bao Loc is particularly notable.

A Brief History Of Tea.

Chua Trinh

The most common story that you will come across for the discovery of tea is the one about Emperor Shen Nong who happened to be sitting besides some boiling water when a tea leaf fell from a bush or tree into the pot which he then drank with great pleasure. Although many treat this a just another delightful Chinese myths there are, worryingly, still others that report it as an historical fact. There are doubts as to whether Shen Nong even existed and he may well have been a composite character that represented many other individuals. As well as tea, he is credited with the invention of the hoe, plough, axe, wells and irrigation among others. Legend has it that Shen Nong had a transparent stomach and would use this to research the affects of various plants on the body. Whenever he had ingested a poisonous one he would drink tea as a powerful antidote.

An equally unlikely tale from Japan suggests the Bodhidharma (a Buddhist monk) discovered tea after he had been sitting in meditation in China for seven years before becoming so tired that he fell asleep. Angry at his inability to stay awake he sliced off his eyelids to prevent it happening again and threw them to the ground; where they grew into tea trees. After picking some leaves and chewing them he felt energised and concluded that the tea was a perfect accompaniment to meditation.

More probable is that using tea leaves by eating or in a drink was a slow evolution. There is evidence from around the world that early people would have collected leaves from the forest for a variety of medicinal and other purposes. It was a stroke of luck for those living in that particular area of Asia that their leaf was a very special one. Some recent research has unearthed evidence of tea being used over 6,000 years ago in China’s Zhejiang province. Some say that this is proof of 6,000 years of tea culture but I’m not so certain as to whether it is possible to conclude whether tea leaves were being cultivated or simply harvested at the time.

Whatever the origins of tea for recreational purposes it was the Chinese who went on to develop it, through various stages, to the drink that we know and love today. Although there are a few references to tea to be found in old scripts the first detailed writing on tea was produced by Lu Yu in his celebrated work, the Classic of Tea published in the second half of the 8th century. At the time of writing the method for making tea was very different from today. The leaves were steamed, crushed in a mortar, made into a cake, and boiled together with rice, ginger, salt, orange peel, spices, milk, and even onions. On second thoughts maybe we are coming around full circle on the evidence of the exotic flavoured blends that are now available.

The Classic of Tea consists of three volumes and ten chapters which cover the nature of the tea-plant, gathering and collecting leaves, tea equipment, method of making tea (he encouraged the elimination of all other ingredients apart from salt), choice of water and the famous tea gardens of China. According to Lu Yu the best quality of the leaves must have “creases like the leathern boot of Tartar horsemen, curl like the dewlap of a mighty bullock, unfold like a mist rising out of a ravine, gleam like a lake touched by a zephyr, and be wet and soft like fine earth newly swept by rain.” Something to bear in mind when you are next in supermarket!

In the 10th century whipped tea came into fashion and created a second school of tea. Leaves were ground to fine powder using a small stone mill, and the preparation was whipped in hot water by a bamboo whisk. At this stage salt was discarded forever.

Powdered tea remained the range for several hundred years until in the mid 14th century taste changed once again and the infused tea leaf method we use today become the norm. Of course, powdered tea lives on with the popular Japanese matcha. The conversion to infused leaf coincided with tea becoming available to all rather than being the preserve of nobility, monks and scholars. It would also not be long before Europeans got in on the act.

Tea seeds had been taken from China by Buddhist monks to both Japan and Korea in the 9th and 10th centuries and cultivation began in both countries soon afterwards.

The first contact with for Europeans were Portuguese traders at the end of 16th century and by the early 17th century they and, more especially, the Dutch were importing tea to their respective countries and became popular with the upper classes and at royal courts. Tea was first sold in London in 1657 (imported from the Netherlands) but by 1664 the British East India Company was importing its own tea from China. In Britain, it was the restoration of Charles II to the throne and his marriage to Catherine of Braganza, a Portuguese princess, that had the greatest impact on the tea trade. Part of the dowry that Charles received on marrying Catherine, apart from some chests of tea, was the port of Bombay (Mumbai) which became pivotal to British trade in the far east through the East India Company, with significant implications in both India and China.

During this period tea became very popular in Britain and spotting an opportunity it was subjected to heavy excise duties which resulted in both the growth of brutal smuggling gangs and ultimately to the American War of Independence. Tea had been introduced to America by the Dutch and remained a popular drink up until the Boston Tea Party in 1773, one of the events leading up to the revolution. Following independence coffee became the drink of choice in the United States.

As the demand for tea continued to grow supply was still closely guarded by China with cultivation and production expanding to more provinces including the introduction of tea plants to Taiwan in 1697. The demand for tea (as well as silk and porcelain) from China was placing an enormous strain on the finances of the East India Company as they had to pay for everything in silver. To overcome this one-way flow of silver the Company initiated a scheme to sell opium from its plantations in India, through middlemen, to the Chinese. In response to this reverse flow of silver and the increasing number of opium addicts the Chinese authorities attempts to stop the trade ended with them seizing supplies and closing foreign concessions in Canton. And so began the first of the Opium Wars in 1839 which had several legacies including the cession of Hong Kong and opening up China to foreign merchants.

Despite it’s military success against China Britain needed a longer term alternative for the supply of tea and India seemed the obvious choice. In 1823 it had been discovered that indigenous tea plants were growing in northern Assam various initiatives were set up to establish a tea industry in India. The most famous of these were the travels of Robert Fortune whose life is excellently documented in the book For All The Tea In China by Sarah Rose. Fortune was employed by the East India Company as an industrial spy to go undercover in China and find out all he could about tea growing and production. He returned with a booty of seeds, cuttings but more importantly the know-how of what to do with the leaves once they had grown. Fortune’s efforts were an important catalyst for the Indian tea industry and in the latter part of the 19th century tea production was expanding quickly in both Assam and Darjeeling.

Elsewhere, the Dutch had introduced tea to Java, Indonesia in 1826 and the British started plantations in Sri Lanka (1867) and Kenya (1903).

In Vietnam, tea culture was largely influenced by that which had developed in China. For almost one thousand years up until the middle of the 10th century China ruled large parts of northern Vietnam. It was a period that saw a strong Chinese desire for cultural assimilation on one side and fierce Vietnamese resistance to foreign domination on the other. The Vietnamese eventually regained independence but legacies of religion, language, traditions, culture and a love for tea remained.

Despite the presence of tea as an indigenous plant and that it had spread throughout the mountainous north by the migration of ethnic minority groups (such as H’Mong and Dao) there was no significant domestic tea industry (note: a few historic texts do reference tea cultivation in parts Vietnam in the 18th century) until after the French occupation and during the ensuing colonial period. The first tea gardens were established in 1890 at Tinh Cuong, Phu Tho province in the north and Duc Pho, Quang Nam province in the south. In the early part of 20th century, research centres were established at Phu Tho, Pleiko in the central highlands and Bao Loc in the western highlands. Development was rapid in the years leading up to the Second World War but the industry was effectively destroyed by decades of successive conflict from the Japanese invasion in 1940 to the end of all hostilities in 1975.